| Finance ministers from around the world will converge on Washington, DC this week for the International Monetary Fund and World Bank spring meetings, as the Trump administration attempts a spree of negotiations with its trading partners. But those bilateral talks will be clouded by sinking prospects for the global economy. For US trade partners, the gloomy global outlook matters — regardless of the rate at which they are tariffed by Washington. “Many countries will be indirectly hit if US tariffs substantially weaken the economic prospects of their trading partners,” says Karen Dynan, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute and an economist at Harvard. Expectations for global economic growth are souring since Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” announcement. At a Peterson Institute event last week, Dynan downgraded her forecast for global growth in 2025 to 2.7% from 3.2%, and 82% of investors surveyed by Bank of America this month expect the global economy to weaken. Goldman Sachs now expects year-over-year global GDP growth of just 1.4% in the fourth quarter — less than half of the 3% growth at the end of last year. The IMF will slash its own growth forecasts when it publishes its World Economic Outlook on Tuesday. “Our new growth projections will include notable markdowns but not recession,” Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said on Thursday. All of this means that even countries optimistic about securing a trade deal with the US will be keeping an eye on the global outlook. Say you’re Japan, one of the nations the Trump administration has prioritized in its negotiations. Its two biggest export markets are China and the US — followed by South Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, Vietnam and Mexico. In 2023, Japan exported slightly more to those last five combined than to the US. Japanese exporters would of course prefer lower US tariffs. But high tariffs on China and Vietnam and Mexico — and attendant dents in those economies — could hurt Japan, too. “Trade wars are contractionary for the world economy, and they are also difficult for central banks to manage,” says Kimberly Clausing, also a senior fellow at Peterson. “A global recession is a particularly daunting problem since every country’s reduced demand further harms other countries’ export sectors.” In other words, in a tightly knit global economy, even bilateral trade fights can have ripple effects. What else to watch for during IMF-World Bank week: - Analysts will be paying close attention to which risks the IMF highlights in its Global Financial Stability Report, due out on Tuesday. “One area they will certainly look at is the US bond market that was under quite a bit of strain two weeks ago,” says Martin Mühleisen, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a former IMF official.

- Dynan said she’ll be watching for any discussion next week on the role of the dollar. “People have been surprised to see it weaken in the wake of the announced higher tariffs and are raising questions about whether the weakening is reflecting a loss of appetite for US assets,” she said.

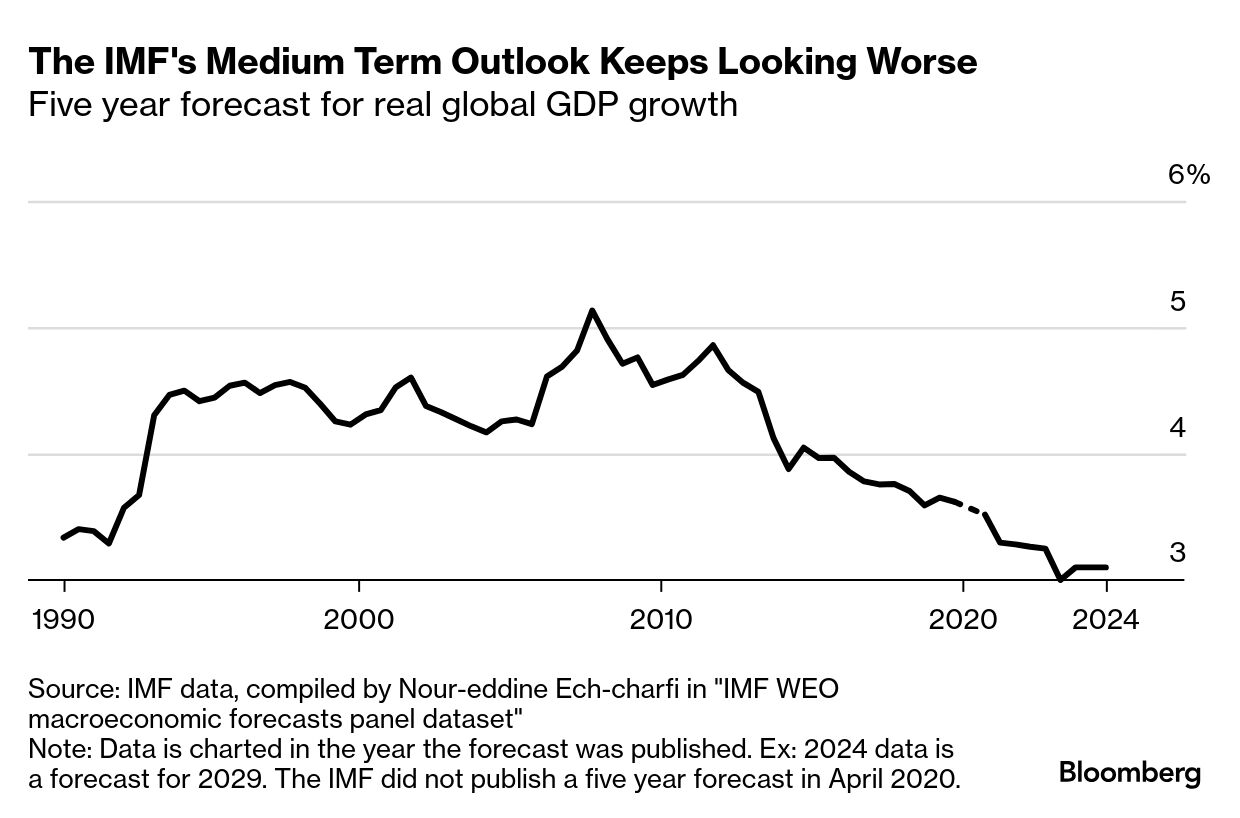

- One more data point to watch is the IMF’s five-year forecast for global growth, which has grown steadily weaker in recent years. “I think it’s quite possible that the IMF medium-term outlook will be less positive,” says Dynan, though by how much depends on the assumptions the IMF makes about tariffs. “There was some optimism among forecasters last year that we might be heading for a brighter outlook given productivity-enhancing technologies like AI,” she says. Instead, we might see the most pessimistic medium-term forecast in decades.

— Walter Frick, Bloomberg Weekend (Disclosure: I was previously an editor at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.) |