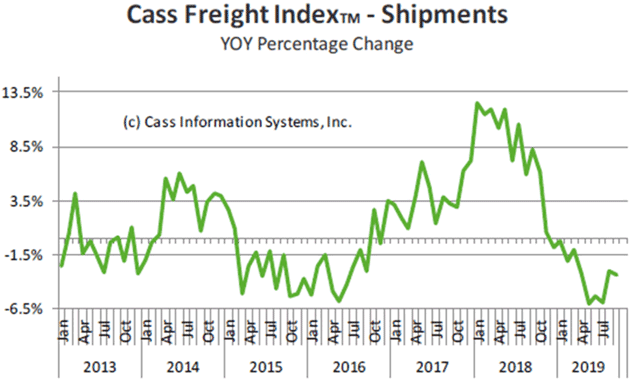

Slowing but Not Stopping (Yet) By John Mauldin | Nov 09, 2019  If you are a computer (other than the newest experimental quantum ones), your world is entirely binary. Everything is some combination of zeroes and ones. The machines can do marvelous things with those two digits but they have limits. We humans don’t have to think in either/or terms, yet we often do. I see it in the economic outlooks that cross my screen. Some forecast imminent doom, others endless boom. But in reality, there is lots of room between the extremes. I’m known as the “Muddle Through” guy, which is another way of saying I think “both/and” instead of “either/or.” We can have both a successful outcome and difficulty getting there. And that’s been my economic outlook for a long time. We are entering a rough period and eventually recession will come, but it will be survivable. The real damage will come in the “echo” recession that I think will follow. Policy changes, mostly of the political backlash type, will ensure the mid-2020s won’t be fun. Ray Dalio just wrote another piece that I will excerpt and link to below, but I was struck by how similar our worries and concerns are. We are approaching a crisis unlike anything we have ever seen, what I term The Great Reset, without any kind of realistic plan. But that is more than a few years down the road. Today I want to focus on that “entering a rough period” part that comes first. The signs are growing clearer and the bumps bigger. For now, the global slowdown is less visible in the United States. That doesn’t mean it will never reach us. It just means others are further down the road we are all traveling. Germany, for instance, may already be in recession. GDP there dropped 0.1% in this year’s second quarter, with little reason to expect better from Q3 which we will learn next week. (Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth constitutes recession, by some definitions.) Whatever you call it, Germany is certainly not in a good spot. It is highly dependent on exports which, for various reasons, are weakening, particularly in their auto industry. The entire euro currency project, while well-intentioned, ended up being essentially vendor financing for the rest of the continent to buy German/northern European goods. It went too far, as we saw with Greece, and now Germany’s best customers are in debt up to their eyeballs and in no position to keep buying. Meanwhile, Brexit (depending on how it ends) could greatly reduce UK purchases of German goods. On top of that, uncertainties induced by President Trump’s trade war are deterring businesses in Europe (as well as here) from investing in future growth projects. And overarching all of it is the technology-driven decline in globalized manufacturing. Production is moving closer to consumers, which will have many advantages, but also create problems for export-intensive economies, especially the emerging-market economies that supply inexpensive labor. Such work is increasingly being automated and moved closer to the actual customer. Which, as we will see below, is visible in the data. If Germany’s “technical recession” morphs into a real recession, the rest of Europe will certainly follow. And recession in Europe—and the measures its central banks will take to fight it—won’t leave the US economy unscathed. Not coincidentally, commodity-producing emerging markets are also experiencing difficulty. Ditto for some more advanced commodity exporters like Australia and Canada. Their problem springs from lower commodity prices, but more specifically from China. Sam Rines explored this in a recent note. Much of the commodity price pressure can be blamed on slowing Chinese growth, but that is not the entire story. China is roughly 20% of global GDP on a PPP basis, and constitutes much of the incremental growth in the global economy. When China's growth slows, the ripples are felt in many places. Commodity prices and China's growth rate are understandably intertwined, and that may be a difficult correlation to break down. Why? It is difficult to pinpoint the next major tailwind. And—even when speculating on the next tailwind—timing is a further difficult hurdle to overcome. But why not try. Of the three major headwinds to commodity pricing in the post-dual stimuli world (end of China's building spree, US dollar following QE, and slower overall global growth), the US dollar is the most likely to abate as a headwind in the near-term. Global growth is dependent largely on US and China trade policy, but there could be a marginal shift higher in growth (the worst might be over). Replacing the rapid growth of China is not easy to see. India is gaining share of global GDP. But it is not easy to see the path to a full replacement of the China commodity cycle. We may soon see the other side of China’s growth story. Just as it had an outsized effect on global GDP on the way up, it will likely be a major drag on the way down. Note, when my young friend Sam says “the worst may be over,” he is talking in particular about the downturn from slower Chinese growth. If you read his daily missives, as I do, he is far from predicting a US recession. Slower growth? Yes. It sounds like he thinks we are in a slower muddle-through world for the next few quarters at least. And maybe through the next elections… While more goods are delivered electronically and supply chains are shrinking, the movement of physical goods is still the economy’s circulatory system. Just as low blood pressure is a problem, so is lower freight volume. And unfortunately, that is what’s happening. Remember that I said we can see less export-driven manufacturing in the data? I think it is here, though hidden within the actual global recession, and we will look back and realize it was localized manufacturing having a visible effect. The Cass Freight Index is the most comprehensive, high-frequency indicator of this. It tends to lead the economy by a few quarters but has signaled almost every economic turning point. So the fact its year-over-year change has been negative every single month since December 2018 is more than a little concerning. As you can see from the data, there have been periods of negative growth without a recession, but the latest drop’s sheer magnitude and rapidity is eye-opening. Sidebar: Recessions often happen after businesses become too optimistic, with what Keynes called “animal spirits” soaring. They expand and then find out they have to pull back. And just as they might’ve been a tad too exuberant on the way up, they become too pessimistic on the way down, cutting production and capacity. This same zeitgeist, multiplied by millions of businesses worldwide, creates recessions. Recessions are an odd thing. We fear them, and if you are a typical hourly worker, rightly so. But a recession is technically only two quarters of negative growth that may be just a little less than the recent peak. I have managed private businesses or partnerships for 45 years. By that definition more than a few of my businesses have been in recession far more frequently than the national economy. Today a few of my income streams are in roaring bull markets while others lag or fall way behind. That’s fine up to a point. If the aggregate starts looking more negative I become more defensive. I look at overhead and expenses a great deal more carefully. I have learned to temper my normal optimism when the numbers are telling me something different. I think that attitude, coming from experience, is common in businesses all over the world. As the infamous Texas Judge Roy Bean purportedly said, “Nothing focuses the mind like a good hanging.” In today’s world, nothing focuses the mind like a few negative quarters. But back to the main story…

Source: Cass Information Systems The chart is through September. The next Cass report, covering October, will be out in the next week, but at this point it would take a heroic move to change the pattern. Freight traffic is falling and it looks even worse when Cass digs into the specifics. (Over My Shoulder members can view the full report in our archive. It’s 30 pages but we highlighted the main points for you.) From Cass: - “Consistent with disappointing housing starts (down -1.8% YTD) and lackluster auto sales (down as much as -4.8% in April and -1.2% YTD), spot pricing in transportation has declined dramatically.”

- “Airfreight volumes in Europe continue to suggest that the region’s economy continues to cool.”

- “Asian airfreight volumes were essentially flat from June to October 2018, but have since deteriorated at an accelerating pace.”

- “Even more alarming, the inbound volumes for Shanghai have plummeted. This concerns us since it is the inbound shipment of high-value/low-density parts and pieces that are assembled into the high-value tech devices that are shipped to the rest of the world. Hence, in markets such as Shanghai, the inbound volumes predict the outbound volumes and the strength of the high-tech manufacturing economy.”

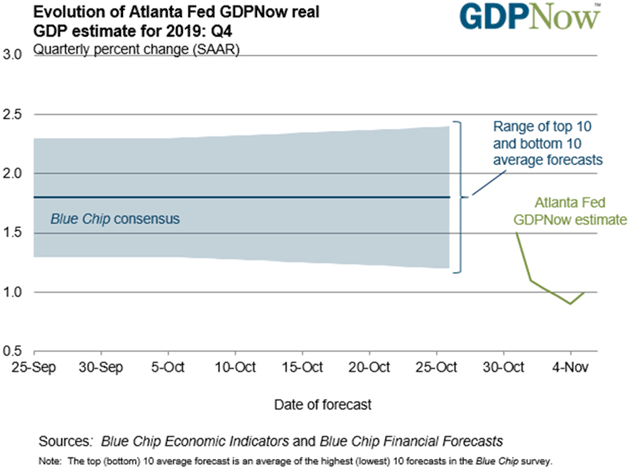

Considering historic correlations, Cass believes its current data signals US Q3 GDP growth will be negative, or close to it. They said that before the Commerce Department estimated Q3 growth was a better-than-expected +1.9%. So maybe Cass was too negative… but there’s still time for the government to revise its number lower, too. And with all due respect to the Commerce Department, the Atlanta Fed “GDPNow” predictions have simply fallen out of bed, down to less than 1% for the fourth quarter, after an anemic third quarter.

Chart: Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank Not to be outdone, the latest New York Fed Staff Nowcast for 2019 Q3 was 1.9% and 0.8% for Q4. Now, 1% GDP growth is certainly not the stuff dreams are made of, especially if you are a Republican looking at a November election cycle. This actually makes me somewhat more optimistic that the various trade issues will be resolved sooner rather than later. All sides have plenty of incentive to stop the madness. Will it change the direction of animal spirits? Fast enough to be reflected in GDP growth by midsummer? That’s anybody’s guess, and I mean just that—a guess. Anybody who thinks they know what some hypothetical trade deal will produce is simply bloviating. Going deeper, Cass notes that “dry van” truck volume is a fairly reliable predictor or retail sales, and is still relatively healthy. That fits what we see elsewhere about consumer spending sustaining growth. But they also note that seasonally, dry van volume should be even stronger than it is. That suggests caution as the year winds down. Other transport modes—rail, flatbed trucks, chemical tankers—indicate real problems in the industrial economy. Manufacturers seem to have little faith consumers will keep buying at the rates they are. And, given how much consumer spending is debt-financed, they’re probably right to be cautious. Strong retail spending is not necessarily positive. Consider this Comscore holiday spending report from November 2007. “The Friday after Thanksgiving is known for heavy spending in retail stores, but it’s clear that consumers are increasingly turning to the Internet to make their holiday purchases,” said Comscore Chairman Gian Fulgoni. “Online spending on Black Friday has historically represented an early indicator of how the rest of the season will shake out. That the 22-percent growth rate versus last year is outpacing the overall growth rate for the first three weeks of the season should be seen as a sign of positive momentum.” The Great Recession began one month after this “sign of positive momentum.” A strong holiday shopping season won’t mean we are out of the woods, and could mean we are just entering them. Ray Dalio has a new post titled The World Has Gone Mad and the System Is Broken. If you think that sounds a bit despondent, you’re right. Sadly, I am in 100% agreement with the headline. We might differ on a few of the details, and some of the solutions, but on the general direction? Not far off. You should read the whole thing but here are some quick excerpts. - “Money is free for those who are creditworthy because the investors who are giving it to them are willing to get back less than they give. More specifically investors lending to those who are creditworthy will accept very low or negative interest rates and won’t require having their principal paid back for the foreseeable future. They are doing this because they have an enormous amount of money to invest that has been, and continues to be, pushed on them by central banks that are buying financial assets in their futile attempts to push economic activity and inflation up.”

- “Because investors have so much money to invest and because of past success stories of stocks of revolutionary technology companies doing so well, more companies than at any time since the dot-com bubble don’t have to make profits or even have clear paths to making profits to sell their stock because they can instead sell their dreams to those investors who are flush with money and borrowing power.”

- “At the same time, large government deficits exist and will almost certainly increase substantially, which will require huge amounts of more debt to be sold by governments—amounts that cannot naturally be absorbed without driving up interest rates at a time when an interest rate rise would be devastating for markets and economies because the world is so leveraged long.”

- “Pension and healthcare liability payments will increasingly be coming due while many of those who are obligated to pay them don’t have enough money to meet their obligations.”

- “Since there isn’t enough money to fund these pension and healthcare obligations, there will likely be an ugly battle to determine how much of the gap will be bridged by 1) cutting benefits, 2) raising taxes, and 3) printing money (which would have to be done at the federal level and passed to those at the state level who need it). This will exacerbate the wealth gap battle. While none of these three paths are good, printing money is the easiest path because it is the most hidden way of creating a wealth transfer and it tends to make asset prices rise.”

- “At the same time as money is essentially free for those who have money and creditworthiness, it is essentially unavailable to those who don’t have money and creditworthiness, which contributes to the rising wealth, opportunity, and political gaps.”

- “Because the “trickle-down” process of having money at the top trickle down to workers and others by improving their earnings and creditworthiness is not working, the system of making capitalism work well for most people is broken.”

The process is pretty clear. Recession is eventually coming and even a relatively weak one will set off the dominoes Dalio describes. We will see highly leveraged, unprofitable companies default on their debts and lay off their workers, sending government debt higher as safety net spending rises and tax revenue falls. To think this happens without a significant bear market in equities is rather implausible. Then public and private pensions will find it impossible to meet their obligations and also impossible to keep disguising that fact. This will force federal bailouts, further aggravating the debt problem. Dalio thinks they will end up monetizing it in some fashion. I think he is right. What we don’t know is the exact mechanism they will use. But it matters a great deal to our response in our personal portfolios and investing. Now consider that, if Cass is right, not to mention the Atlanta and New York regional Fed forecasts, this will unfold in a highly contentious election year, and possibly with the US still embroiled in a trade war with China and/or others. We’ve seen how reports that negotiations are going well, or not going well, can move markets. In a few months we will start seeing similar responses to political poll results. Indications that Elizabeth Warren, for example, might get a chance to implement her wealth tax idea could trigger sharp changes in stock valuations. Bottom line: The economy is slowing and market volatility rising. Looking at the data and seeing further out than nine months is extraordinarily difficult. Yes, the inverted yield curve says recession is coming, but it’s an imprecise indicator. And I am painfully aware that markets can go up significantly (20% or more!) after an inverted yield curve. That being said, we must have our recession antennae raised. Navigating through this is going to be hard. But “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible.” Stay tuned… The good news is I will likely be home until the third week of November when I go to Philadelphia. Then I spend the next week in Dallas for Thanksgiving with family and friends. There are more travel opportunities but also the need to read and write. Books just don’t happen… Speaking of books, writing a book about what the world will look like in 20 years obviously requires a great deal of research and help. And then I have to keep up with what is going on in the real world to write this letter. It is something of a mental whiplash. I totally get that most people focus on the near term (very understandable) but writing about what will happen in the middle to late 2030s puts a slightly different perspective on what the latest Fed move might be. The future of work? Health technology? Age spans? So many things will be different and better and other things will be far more difficult. I am not sure humanity is ready for this much change to happen so quickly. In fact, I am pretty sure we aren’t. Which is why it is so important that we make sure the changes will be positive for us and those who we hold dear. But the key to that, gentle reader and friend, is to not only accept the changes but make changes in your own world as well. And that is never easy… And with that, I will hit the send button and wish you a great week. Your struggling with his own changes analyst,   | John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.    | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|